Poison Hemlock in the High Country…What to Know

go.ncsu.edu/readext?1078117

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

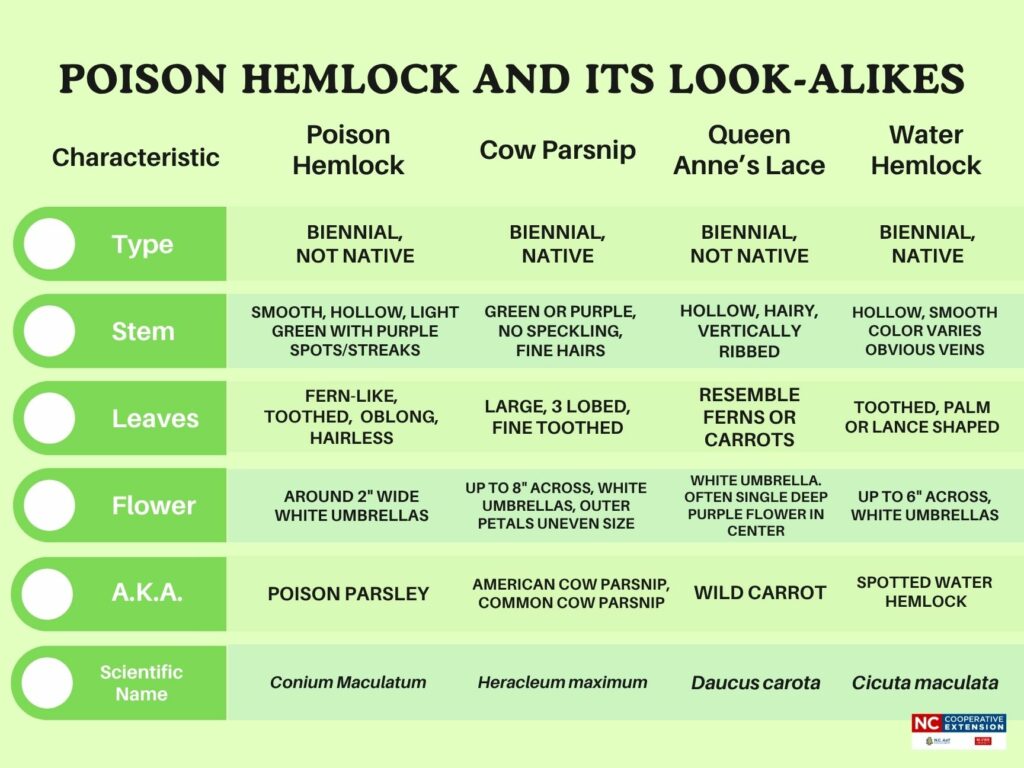

Collapse ▲UPDATE! Check out this new resource comparing Poison Hemlock to a few of its common cousins. You can also scroll to the bottom of this page to view the graphics.

Over the last several weeks, Watauga Cooperative Extension has received a number of calls from concerned citizens and farmers with questions about poison hemlock on their properties. Unlike the tall, dark green hemlock trees which are commonly found in our native Appalachian forests, poison hemlock is a highly toxic flowering plant that can grow 3 to 10 feet tall. It has clusters (or ‘umbels’ if you want to use the PhD word) of small white flowers, which look a LOT like Queen Anne’s lace, Cow Parsnip, and a few other plants in the high country. Poison hemlock is actually a fairly common plant here in the High Country that can be found typically in open, weedy & grassy areas near streams, creeks, and other damp places. It is also a prolific seeder, so it’s possible that the raging floodwaters caused by Hurricane Helene dispersed and deposited additional seed in our sandy, bottomland floodplains, which has made them more noticeable this year.

Poison hemlock is a biennial plant—it grows as a small rosette its first year and flowers out in its second year. With so many reports coming in, it sounds like this is a big ‘flowering year’ for poison hemlock. While other toxic species like giant hogweed are on the federal noxious weed list and have eradication mandates due to their threat to public safety & agriculture, poison hemlock is not. Therefore, if you have it in your fields or on your property, it’s a good idea to know how to identify it and be cautious if you choose to get rid of it.

How do I tell it apart from other, similar plants?

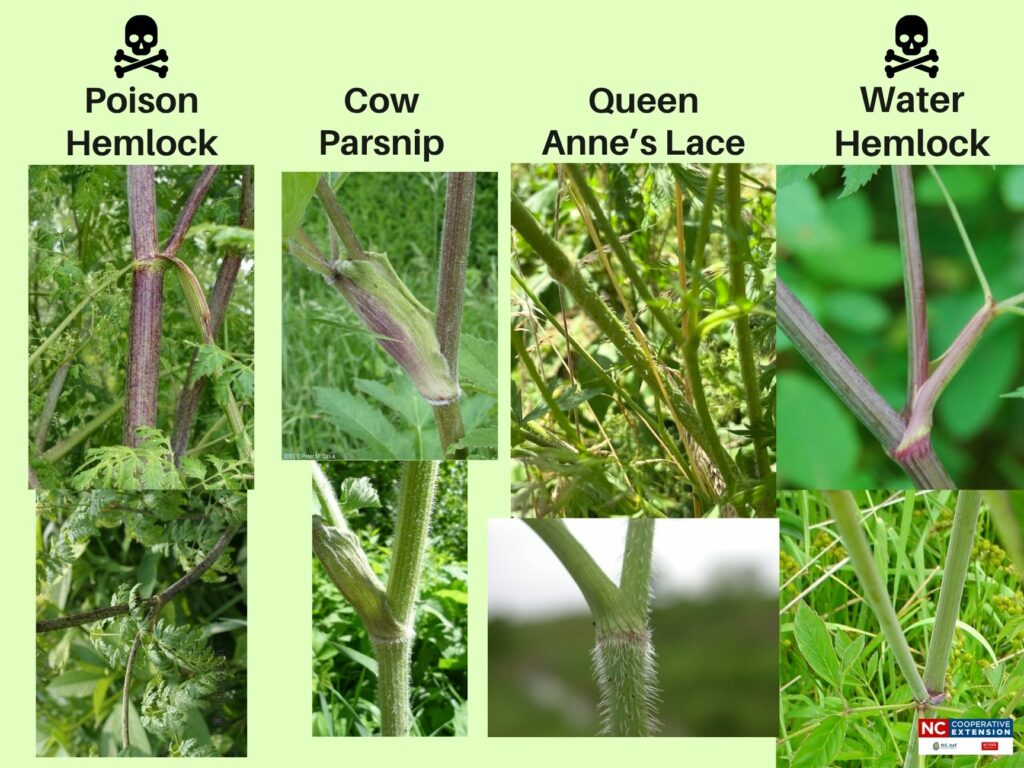

Poison hemlock has smooth, hollow stems with purplish spots and streaks—while Queen Anne’s lace has hairy, green stems—which DON’T have any purple streaks.

Queen Anne’s lace stems (left) are hairy and green. Poison hemlock stems are smooth with purplish streaks & splotches

Queen Anne’s lace rarely gets above 3 feet tall, while poison hemlock can be much taller—up to 10 feet! However, the leaves of both plants look very similar—like carrot leaves…they’re in the same plant family as carrots. But while poison hemlock’s leaves are bright green, more lacy and hairless, Queen Anne’s lace have slightly grayer & hairy leaves.

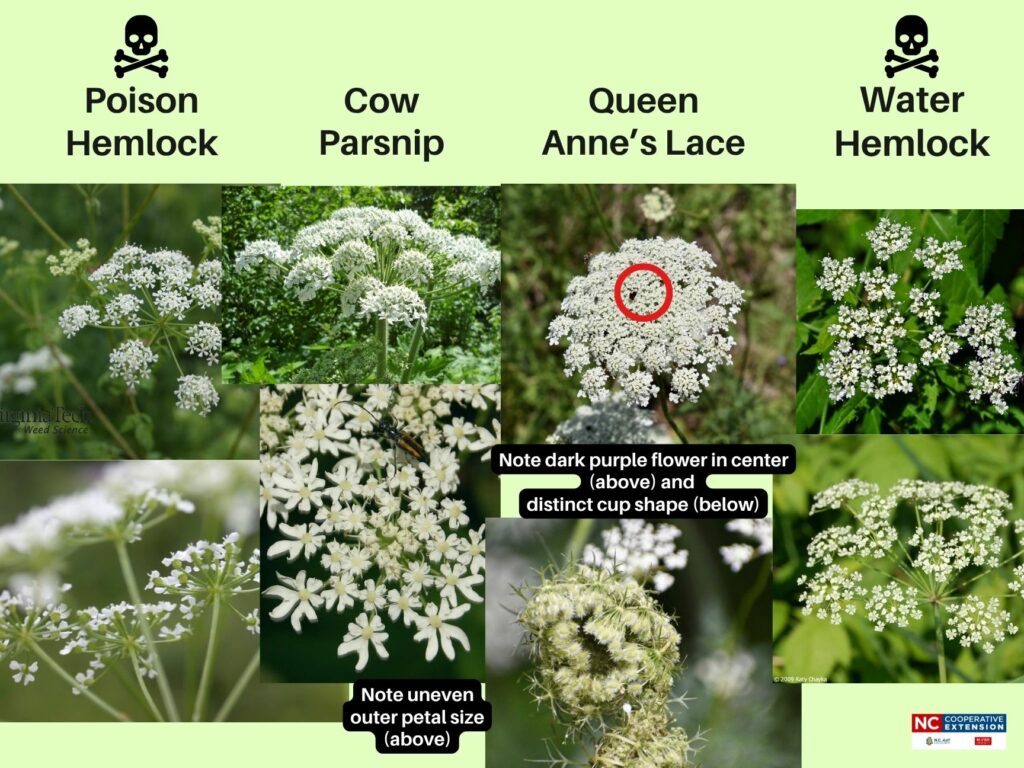

The flowers of each of these are a little different, too. While Queen Anne’s lace has small, white petaled clusters of flowers similar to hemlock, its clusters are flatter, while poison hemlock’s flower cluster is usually more rounded and ‘umbrella shaped’. Also, Queen Anne’s lace will often have a dark purple flower in the middle of its flat cluster—the folk story goes that “Queen Anne pricked her finger while sewing the lace, and a single drop of blood stained that middle flower”. Poison hemlock will NOT have that center, purple flower.

Queen Anne’s lace flowers are flatter (left) than poison hemlock flower clusters (right) which are more rounded & ‘umbrella-shaped’ (photo courtesy of Ohio State Extension)

There’s also another tall flowering species common to the high country that also produces large clusters of flowers…cow parsnip. However, its leaves and flower heads are MUCH larger. We have a lot of that species growing around Watauga County as well (especially in the Brookshire area and greenways).

So…How toxic is this stuff?

Poison hemlock has several toxic compounds, or alkaloids, which, if ingested, can cause a whole list of nasty symptoms like vomiting, tremors & seizures, muscle paralysis, kidney failure, and even death. There is no antidote for it. You might remember that Socrates, the Greek philosopher, famously was sentenced to death by drinking a poison hemlock concoction. As toxic as it is, though, we haven’t heard of any reports of hemlock poisoning here in western North Carolina, lately. Poison hemlock is really only POISONOUS if ingested. However, you should definitely be careful HANDLING poison hemlock as well. Its sap can cause contact dermatitis & rashes (similar to poison-ivy), so gloves are recommended if you choose to cut & remove it. Small infestations of the plant can be removed by digging up the plants before they begin producing seed (spring and early summer) and disposing of them away from the active part of your property. If they’ve gone to seed, you should bag them up and dispose of them in the trash. Certain herbicides can also be used to manage larger infestations. And dead material should also be gathered up and disposed of properly to avoid any accidental exposure.

What about my livestock?

If poison hemlock is identified and/or prolific in your area, you should definitely keep an eye out and manage it. Poison hemlock is toxic to all livestock that may accidentally ingest it while grazing. So, if you’re growing hay to bale or silage or grazing your animals on a bottomland field, it’s important to remove or treat any poison hemlock that might be there. Even the dried stems of the plant can remain toxic for a long period of time—so, you don’t want that in your hay. If you have questions about management for this plant in your hay/grazing fields, contact Kendra Phipps, Watauga’s Livestock Agent: kendra_phipps@ncsu.edu